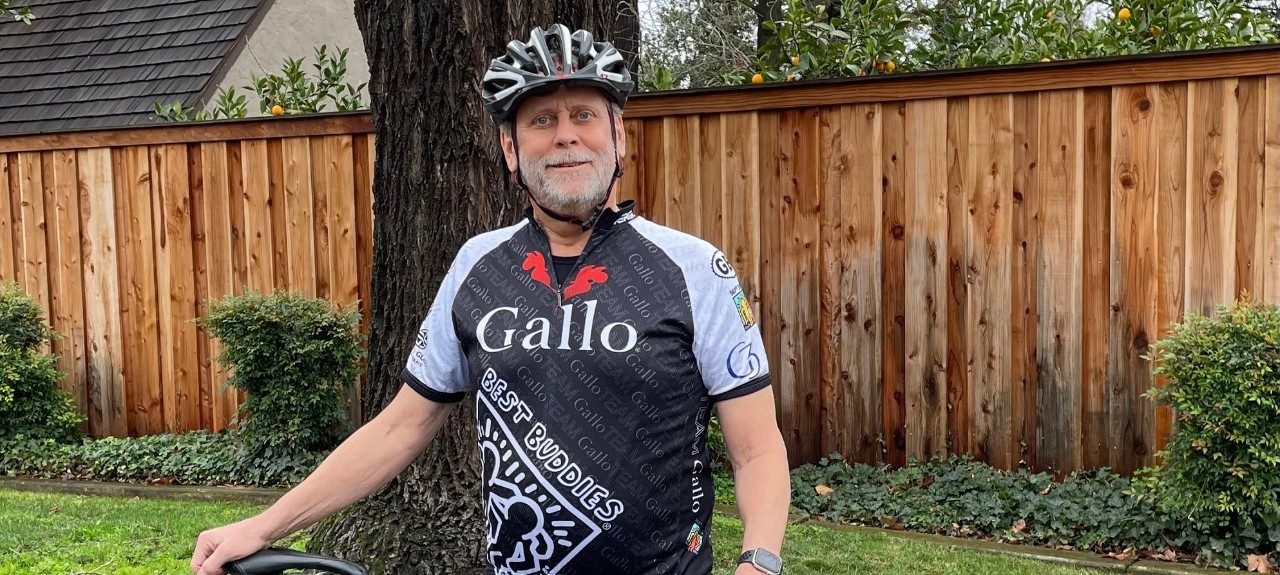

Tom Pugh, patient

Our Patients

More, better, faster: A standout year for Stanford Health Care’s heart transplant program

05.28.2021

By Ruthann Richter

Tom Pugh got the call while on a midday Zoom meeting for work. “We have a heart for you. Do you want it?”

It was the culmination of a seven-month medical ordeal. During that time, the research scientist suffered two heart attacks, the second so severe it nearly cost him his life; spent 65 days in intensive care; underwent surgery to have a mechanical heart pump implanted; and engaged in rehab and a home “boot camp” of stair climbing and stationary bike-riding to regather his strength so he could withstand a heart transplant.

And then came the Nov. 12 call from Stanford Health Care, where he received what cardiothoracic surgeon Joseph Woo, MD, called a “snappy” new heart, one to match Pugh’s high energy.

“I have a lot of angels on my side,” said Pugh, 62, a microbiologist and avid cyclist from Modesto, California. “I’m a very lucky person.”

CARE AT STANFORD

We’re recognized worldwide as leaders in heart failure care and heart transplantation, achieving excellent outcomes with shorter-than-expected wait times.

650-723-5468

He joined 85 other lucky people in 2020 in a record-setting year for Stanford Health Care’s heart transplant program.

“We transplanted more patients, we transplanted them faster and we have been getting great outcomes,” said Jeffrey Teuteberg, MD, chief of heart failure, cardiac transplantation and mechanical circulatory support at Stanford Health Care. “It’s a fantastic combination.”

Continuing apace despite pandemic

Jeffrey Teuteberg, MD

While the COVID-19 pandemic forced some transplant centers to temporarily slow or even shut down, Stanford Medicine’s program continued apace, as the medical center maintained enough beds for patients, who were housed in an isolated unit, and established a rigorous testing program to ensure patient safety, Teuteberg said.

“Fortunately, it had very little impact,” said Teuteberg, an associate professor of medicine. “We were very lucky here in California for most of the year compared with other parts of the country. Even with the current surge, it hasn’t had a major impact on the program.”

Stanford, which pioneered heart transplantation, ranks as the fourth-largest transplant program in the country.

In recent years, Stanford Health Care has averaged about 65 transplants a year. In 2020, the number rose in part because Stanford physicians actively reached out to heart centers in the Bay Area and beyond, resulting in more patient referrals.

Teuteberg said overall survival rates have been steadily improving in the last several years as Stanford has implemented more standardized protocols and further strengthened measures aimed at quality improvement. For those who received new hearts between July 1, 2017, and Dec. 31, 2019, more than 95% lived at least a year, according to statistics compiled by the national Scientific Registry of Transplant Patients. Stanford did better than expected, as the registry projected that only 91% would survive a year, based on characteristics of the donors and recipients.

“I think we have gotten better at selecting patients, managing them, getting them through the transplant process and monitoring them in the post-operative period,” he said.

At the same time, he said the program has been gradually shortening the amount of time that transplant candidates have to wait for a new heart, thus reducing the number of deaths among wait-listed patients.

We transplanted more patients, we transplanted them faster and we have been getting great outcomes.

The shorter wait times were related in part to a new system initiated by the United Network for Organ Sharing, the nonprofit that manages the nation’s organ transplant system. Under a new protocol, the network places patients into one of six categories, instead of one of three categories, based on the severity of their illness. That helps medical centers identify the most acutely ill patients in immediate need of a transplant and match available organs to them faster.

Shrinking waitlist

The wait time for undergoing a heart transplant at Stanford Health Care last year averaged about three months — better than other heart transplant centers in the Bay Area and nationally — with some of the sickest patients receiving transplants in as little as a week, Teuteberg said.

“Our waiting list typically has been small and has been getting smaller because we transplant people so quickly,” Teuteberg said.

The national registry figures also suggest that Stanford is capitalizing on the available pool of organs, which unfortunately are still in chronically short supply. Transplant centers generally evaluate organs on the basis of several factors, such as the pumping ability of the donor heart, the donor’s age and the distance to travel to retrieve the organ. Stanford is 93% more likely to accept an organ than other centers around the country, the national registry shows.

“I would say we’re more aggressive than other centers,” Teuteberg said. “I think there are lots of good organs out there, and some centers may not take them because they are farther away or organs may be from an older donor, but they are perfectly fine organs. We’re expanding the pool by taking advantage of what’s there.”

He said recent improvements in organ preservation also have enabled Stanford to venture farther to obtain donor hearts. Instead of storing them on ice, as was previously the case, the new technology uses below-zero temperatures to preserve them in a kind of suspended animation. That enables a donated heart to remain viable for longer periods of time. The technique has allowed Stanford to collect organs from distant parts of the country — as far away as Alaska, Missouri, the Dakotas and Texas, Teuteberg said.

Pugh said he knows little about his donor, other than the fact that she was a middle-aged woman. The heart had excellent function and began pumping immediately after it was implanted in his chest.

Our waiting list typically has been small and has been getting smaller because we transplant people so quickly.

He’s now adapting to his new life, building up his stamina with 1- to 2-mile daily walks with his wife, Susan, and their new miniature poodle.

“I’m living for the day — carpe diem, enjoying the small things and not taking anything for granted,” he said. “It’s a huge second chance.”